These LSAT Flaws Might Be Aaron Hernandez’s Best Defense

- by

- Jun 25, 2013

- LSAT, Sports

- Reviewed by: Matt Riley

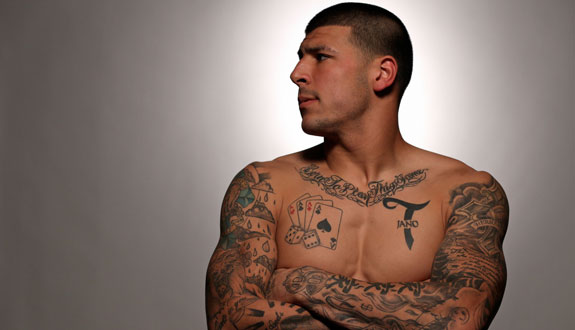

In case you haven’t heard about the investigation surrounding New England Patriots tight end Aaron Hernandez, here’s a quick recap.

Aaron Hernandez and Odin Lloyd, a semipro football player who was dating Hernandez’s girlfriend’s sister, were out drinking one night last week. The two of them, along with two other men, left in Hernandez’s SUV. Later, there were only 3. Lloyd’s body was found a mile from Hernandez’s home the next day. He had been shot, execution style.

Then the investigation began. Police discovered that Hernandez had destroyed his house’s security system, which could have recorded video. Asked to hand over his cell phone, Hernandez complied. But the phone was in pieces. Neighbors reported that a team of house cleaners visited the day after Odin’s death.

Authorities are expected to execute an arrest warrant for obstruction of justice. You may think that the above indicates that Hernandez is guilty, guilty, guilty of the murder. You might or might not be right, but if you’ve reached that conclusion based solely on the above you’re guilty of some LSAT logical fallacies.

Causality: Lloyd was with Hernandez. Lloyd was then murdered. Then Hernandez destroyed a whole bunch of stuff that might be evidence. It’s tempting to conclude that Hernandez destroyed his security system and phone to cover his own tracks, because he had something to hide. But we can’t know for sure the causal relationship between these events, especially if this were on the LSAT. It’s possible that Hernandez was just covering for one of his buddies. The destruction of evidence would still be deplorable, but Hernandez might be guilty of far less than many assume.

It’s also technically possible that it’s all a coincidence. Maybe, after wishing Lloyd an innocent goodnight, Hernandez became enraged at all of the electronic devices that were taking over his life. And then decided his house needed a good cleaning. OK, I wouldn’t believe that and I wouldn’t expect you to. But it’s at least possible.

Equivocation: Hernandez has been the focus of the investigation. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that he did it, or even that police think he did it. Watch out for shifts between related, but distinct concepts like these on the LSAT. The police might think that the evidence he destroyed is really important, and might be after any shred they can find, but they might think the evidence will implicate one of his friends. Or they could be on the wrong track entirely. Remember the case of Richard Jewell?

I doubt any of you, die-hard Patriots fans aside, are the least bit convinced of Hernandez’s innocence after reading the above. That’s OK. If you asked me, I’d say he looks guilty as hell. Which brings us to an important point in relating this to the LSAT: an invalid conclusion doesn’t have to be false. In other words, if you reach a conclusion through logic that’s less than perfect, you haven’t proven that conclusion true. But on the other hand you haven’t done anything to indicate that the conclusion is false. If you treated the above as evidence of Hernandez’s innocence, you’re guilty of an absence of evidence fallacy of the type the LSAT might call treating a failure to prove the truth of a claim as evidence that the claim is false.

Search the Blog

Free LSAT Practice Account

Sign up for a free Blueprint LSAT account and get access to a free trial of the Self-Paced Course and a free practice LSAT with a detailed score report, mind-blowing analytics, and explanatory videos.

Learn More

Popular Posts

-

logic games Game Over: LSAC Says Farewell to Logic Games

-

General LSAT Advice How to Get a 180 on the LSAT

-

Entertainment Revisiting Elle's LSAT Journey from Legally Blonde